Story by Harold R. Thompson

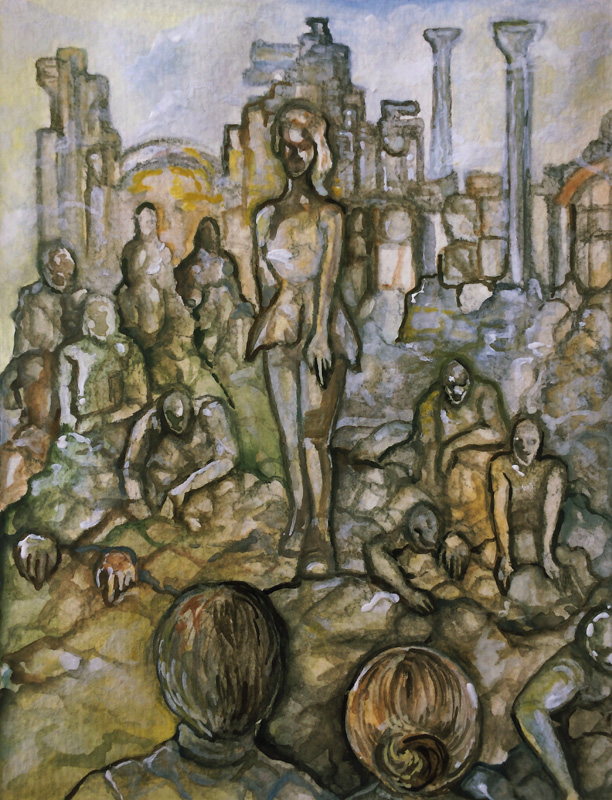

Illustration by Carol Wellart

They call me Lucky Sam, but I only started flipping a coin as a sort of joke, or maybe a test, and it became a habit, and now I use it to let my luck guide me. Or I pretend to, as in the time Mrs. Harcourt asked me to join her expedition to the Vanishing City.

Heads I join, Tails I don’t.

Heads.

Would I have joined anyway? Return to the place that had taken my mother from me, maybe find some sign of what really happened to her?

My mom gave me the coin, a relic from one of her expeditions. An ancient gold coin from the reign of King Jarrot II. Fat and heavy in my pocket.

Of course, I would have gone anyway. Luck had nothing to do with it.

Now I’m thousands of miles from home, in the barren country west of Valgurnia, sweating in the sun despite my wide-brimmed hat, wearing out my new leather boots on the rocky floor of a narrow pass through the hills. My companions include Mrs. Harcourt, stout and determined and in charge, dressed in a leather jerkin despite the heat, and a local woman named Vilna who, with the aid of two taciturn assistants, leads our three pack mules. Gerard Malle, an old friend of my family’s, an expert tracker and crack shot with an air rifle, gives us six.

The Vanishing City has yet to appear, but it will show itself tomorrow.

We camp in the pass, even chance a fire. The Valgurnians guard all other approaches to the City, their government having laid claim to the treasure, but my mother and Mr. Harcourt were convinced that no one else knew about this secret way. It was theirs.

Mrs. Harcourt has a map unrolled on the ground in front of her, the map her husband had drawn during his first expedition.

“Let’s not lose sight of why we’re here,” she says.

I lean against the rock wall of the pass, my arms folded across my chest. We’re here for the loot, for the treasure that the Emperor of Tarmoff amassed during his conquests. Mrs. Harcourt’s husband had discovered an untouched vault filled with gold coins and bars on his first expedition, but he’d lacked the means to remove most of his find. Seven years later he’d returned, better prepared, but something had gone wrong. He and his team had never come out of the City.

My mother had been a member of his team.

“I don’t know if I care about the loot,” I say.

I can see my mother as she last looked, with the mountain star she always wore in her hair. I’d been thirteen.

“You’re giving up your share?” says Gerard from the other side of the fire where he’s cleaning one of his air rifles. He gives me one of his mocking smiles. I don’t like it. I’ve always thought he had a cruel streak.

“Of course not,” I say.

That money should have been mine already, my inheritance.

“We both have other reasons for coming here,” Mrs. Harcourt says, and from her, I sense nothing but kindness and understanding. “Not that I expect our loved ones to reappear, because they won’t, but we have something to finish, in their honor. And I’m glad you’re along because you’ll bring us luck. Right?”

I’m still thinking about my mother, and shrug.

“Some luck,” I say. “Lost both my parents before the age of sixteen.”

Mrs. Harcourt is nodding, but says, “It’s the good luck inside the bad.”

I meet her eye and instantly grasp her message. I was never thrown on the street. I had people who cared for me. I went to the best schools and was now an assistant professor of history at Ark University. And just twenty-one.

Twenty-two next month, and about to secure a fortune.

I regret my moment of self-pity.

It’s cold in the pass that night, and I don’t manage to sleep until very late. Gray daylight awakens me. Too soon. I yawn as we break camp and trudge the final few yards of the pass. We emerge above the bowl-like valley where the City once stood, but all I see is grassland and a narrow meandering stream. I half doubt what’s about to happen.

“We wait,” says Mrs. Harcourt. “An hour maybe.”

The mules crop the grass and the muleteers chat in their own language. Gerard hands out weapons, giving me an air rifle and a leather pouch of ball ammunition. I already have my falchion, hanging from my belt, and think that should be enough, given that weeds may be our only adversary.

“You never know,” Gerard says. “And wild animals may wander in.”

I sling the rifle over my shoulder, its strap biting into my flesh under my flannel shirt. As I’m adjusting it, trying to find a comfortable position, the City appears.

It’s just there, a spread of streets and buildings filling the valley. It’s like waking from a dream, or falling into one, or being transported from one place to another in an instant. I stop what’s I’m doing and stare, my senses overwhelmed. We’re on a slight rise, so we can see the tiled rooftops, the gray limestone buildings. Five tall towers stand in a ring about a mile out from the palace, which is dead center. The streets are like the strands in a spider web, concentric circles, and long straight connectors.

“Tarmoff,” Gerard says, his voice soft. “Every seven years, for four hours. An empty city, filled with gold.”

Mrs. Harcourt gazes at the City without expression.

“Let’s go,” she says.

Vilna barks a word to the muleteers, and they start down the slope to what looks like the back gardens of a suburb, square stone houses with pitched roofs, surrounded by low stone walls, each with a little wooden gate.

It takes me a moment to move my legs, and I have to jog to catch up.

Soon we’re in a cobbled street. There’s no sound but the wind and our footfalls, the occasional snorting of the mules.

“What about the Valgurnians?” I say.

“They won’t come in,” Mrs. Harcourt says. “Their claim to the treasure is still making its way through the Court of Trade, and I doubt it’ll be successful. But it’s not so much international law keeping them out as the fact that they fear the place. And guards caught looting will be shot.”

“What about us?”

“We get in, we get out. And don’t be surprised if we encounter other prospectors. We’re not the only ones crazy enough to sneak our way back here.”

“We need to move,” Gerard interjects. “We have less than four hours.”

We steer straight for the heart of the city, making our way along one of the long avenues. Plane trees, in full leaf, line one side, and spindly lamp posts, all copper green, line the other. The houses are gray limestone, five or six floors each, and in good condition for the most part, though here and there I see a crumbled wall or a large crack in the masonry.

“I want to take a look,” I say, making for a gaping doorway.

“We’re not stopping for you,” says Gerard.

One of the mules snorts.

The heavy wooden door to the house, carved with leaves and flowers, is intact but stands open. Inside I see a staircase with an iron banister, and to the right, a well-furnished room with green carpets and velvet curtains, low tables, large heavy wooden chairs. It looks as if the owners have just stepped out.

I clutch my lucky coin where it sits in my trouser pocket. The strangeness of this place comes over me all at once, and the hair stands on my neck. I don’t know what luck can do for me here.

Did my mother come down this street, investigate one of these empty houses?

I flee back into the street, my heart suddenly pounding. The others haven’t gone far, and have stopped, despite Gerard’s words.

“Is there trouble?” I say, catching up.

“That sound,” says Mrs. Harcourt.

I hear it, a distant crackling or shuffling. Again, I feel a cold shiver.

“The guards?” I suggest.

“They don’t come into the city,” she insists.

“Are we sure there’s no one living here?”

“Nothing can live here.”

I know this is true. I know the story of this place, how the emperor told his magicians, what we’d call scientists, to protect the city, to protect his plunder. They’d built the ring of five square towers, boasted that they would harness the energy of the city’s people, their living energy, to create an invisible shield. Every learned mind on the continent had watched and waited, and when the towers were completed, and the system activated, the city simply vanished.

The magicians had been secretive, and no one knew what they’d done nor where they’d gone wrong.

Seven years later the City had reappeared, but not its citizens. All that gold, now abandoned, brought the first prospectors, doomed adventurers who hadn’t known the City would only exist for a short time. When it vanished again, so did they.

Almost a century later, we know the City reappears every seven years and stays for just four hours. No one lives there and nothing changes. A great deal of treasure has been removed, but no one knows how much remains. Four hours every seven years hasn’t been much time for surveys and studies.

My mother and Mrs. Harcourt’s husband had found a vault larger than most.

“Go left here,” Mrs. Harcourt says. She has the map in her hands.

The buildings here are more like places of work or industry, long low structures, some with fanciful turrets and cupolas. Mrs. Harcourt stops in front of a flat-faced structure with a single large door and no windows.

“This is it,” she says.

There’s something scratched on the door, and I step forward, hoping for some sign of my mother, maybe her name as she staked her claim. But the scratch is simply a large cross, a generic mark.

I place my hand on it.

The pressure is enough to push the door open. Beyond is a large empty room. On the wall to the right are banks of drawers or cupboards. On the left, a stone staircase leads down.

“Let’s get the treasure out,” Gerard says. “I’ve waited a long time for this!”

Vilna and the muleteers remain in the street as we descend the stairs. Gerard has lit a lantern and takes the lead. At the bottom is another corridor, with many doors along one side. One door stands open.

“It hasn’t been touched since Kane was here,” Mrs. Harcourt says. “No one else could possibly have come this way.”

The room on the other side of the door is filled with small wooden chests. This is what we came for.

“Is it all still here?” I say as Gerard and Mrs. Harcourt take stock. “Your husband didn’t remove any of it?”

“It doesn’t look like it,” Gerard says.

Kane Harcourt had mentioned twelve chests of coins. There are twelve chests in the vault. My heart is in my throat. The sum of all this loot is staggering, and no one is here to stop us from taking it out. But I wonder why my mother’s team didn’t manage to take even a single chest.

“What’s in those other rooms?” I say. “Is there more?”

Mrs. Harcourt shakes her head.

“According to my husband, nothing. Either picked clean or they never contained anything. It’s just this one.”

There are tears in her eyes, and she wipes them with the back of her hand as she and Gerard get to work. They’ve been rehearsing this moment for years, and the operation goes like clockwork. I play my part. The mules carry small collapsible leather sleds, and we place the heavy chests on these, attach them to ropes, and slide them up the staircase.

I’m disappointed that my mother left no sign. Maybe she didn’t even make it this far into the City. Despite the extent of the loot, I suddenly feel empty, disillusioned.

Maybe it’s true that I didn’t really come here for the money.

We’ve brought all the chests up the stairs, and now the muleteers are strapping them to our poor beasts of burden, four per mule. As they work, I look around at the lonely street and realize that one of the five towers stands on the other side. I gaze upward. The tower is about a hundred feet tall, its sides made of smooth fitted blocks. There’s a door on the street level but no windows.

I take out my lucky coin. The muleteers will be a few minutes, and I wonder if I have time to investigate, to look inside one of these mysterious and failed wonders. Has anyone studied them? Not to my knowledge.

I flip the coin. Tails mean I investigate the tower, Heads I don’t.

Tails.

As I start across the street, Gerard calls out, “Where are you going? We have less than an hour!”

“I’ll just be a minute,” I call back over my shoulder.

To my right, I catch a glimpse of movement. I pause and look along the street, and there’s that crackling sound again. I think I see a crack suddenly appear in the wall about twenty yards distant, so I make my way there for a closer look. Sure enough, chunks of stone have spalled from a wall between two windows. Dust is still falling. Nearby, there’s a small crater in the street, with several cobblestones displaced, as if a large burrowing animal has been at work.

I stand there, watching, but nothing else happens. Old buildings, I assume, just succumbing to stress, although I can’t fathom what could have happened to the street.

I go back to the base of the tower. Like the building with the treasure vault, the door is ajar. I step inside, waiting for my eyes to adjust to the gloom. The tower seems to contain a single space, stretching all the way to the top, without any floors. In the center is a tall cylindrical shaft that has a faint coppery glint. And, as my eyes continue to adjust, I can see sculptures on the surrounding walls. When I examine these closer, I discover that they’re human figures, clothed in flowing robes or long coats, all entwined together and facing into the wall.

Strange.

As I stare at these baffling features, I suddenly catch a glimpse of my future. I came here to find my mother’s memory, but I’m a teacher of history. No one knows what happened in this place, and no one’s made an effort to find out.

I’ll make that effort.

From outside, I hear several voices raised in alarm, and a woman’s scream, and the baying of the mules. These sounds are full of real danger, and I dash back into the street. I see the two muleteers are holding the pack animals and trying to keep them calm, while Vilna and Mrs. Harcourt stand and stare at a massive crater in the street, larger than the one I’d discovered earlier.

There’s no sign of Gerard.

“What happened?” I say as I approach.

Mrs. Harcourt’s face is white.

“Something came out of the ground and pulled Gerard in,” she says. “Just pulled him under the ground.”

“It was arms,” says Vilna in her heavy accent. “Hands took him.”

This makes no sense, but the solution seems obvious to me.

“Dig him out!” I say.

We brought two small spades with us, and I grab one from where it hangs a mule’s harness, then jump into the crater and start shoveling. I find it hard to believe Gerard was pulled under. The ground is firm and takes effort to move. There’s no sign of a deeper hole or a passage through which a man could have gone.

Mrs. Harcourt just watches me as I work. They all seem stunned.

I hear the crackling sound again, but much closer, behind me. I turn to look as Vilna shouts something in her own language.

Something is coming out of the ground, shoving aside the cobbles, just thirty yards away, something like huge gray worms or snakes.

I realize that they’re arms. Human arms, with hands attached.

The mules bolt, the reins tearing from the grips of the muleteers, who run after them. Arms burst from the street around one of the muleteers and within an instant, he’s gone, pulled under the ground just like Gerard must have been.

“What in blazes,” I shout as I throw down the shovel.

Pulling my air rifle around from where it hangs on my back, I take aim and start shooting. The arms break into pieces as they’re hit, like clods of dirt or clay.

Gerard’s rifle is on the ground, and Mrs. Harcourt grabs it.

“They’re over there, too!” she says.

Human arms are emerging from the street in the other direction. I turn to fire at them as more emerge much closer, from the ground under Vilna’s feet. She’s surrounded by them like strange writhing weeds. I fire, destroying two, then I catch a glimpse of her eyes and know I can’t fire fast enough.

The arms pull Vilna under. She just disappears into the dirt between the shattered cobblestones.

The rifle’s no good, so I draw my falchion just as clutching hands break from the floor of the crater and grab at my trouser legs. I swing the blade and the arms come apart in a spray of earth, and I scramble backward, back up onto to firmer ground where I almost collide with Mrs. Harcourt, who’s firing her air rifle at the things down the street.

There’s no sign of the mules. They’re gone and so is our treasure.

The mules are wiser than we are.

“Run!” I say.

The crackling sound is all around us now. I can run faster than Mrs. Harcourt, but can’t leave her, so I take her plump hand and almost drag her down the long avenue. A fringe of human arms bursts from the ground in front of us, blocking our way like some macabre fence, so I turn into a side street.

We both stumble to a halt. A dead-end. I didn’t know there were any dead-end streets in the City. We’re facing a featureless gray brick wall, with arched windows one floor above.

“What’s going on?” I say to Mrs. Harcourt.

She shakes her head. She’s flushed and gasping for air.

“I don’t know,” she says. “I’ve never heard of anything like this happening before.”

In front of us, the surface of the brick wall cracks. A pair of arms pushes out, though slowly this time. I raise my falchion, but pause, amazed, as a head and a torso emerges, then the full figure of a man, all gray like the stone of the wall, like a statue. He has a short beard and wears just a shirt, a long vest, trousers, and knee-high boots.

I know him from his pictures. Mrs. Harcourt gasps.

“Kane?” she says. “Is that you?”

The figure advances. Behind it, more full bodies emerge from the wall, these with featureless faces.

“Martha,” the figure of Kane Harcourt says. “Come with me. Come and join me.”

The thing holds out its arms.

“It can’t be him!” I say. “It’s something made from dirt and stone -”

“Take my hand, Martha. I have so much to show you.”

The voice is rough but entirely human. Mrs. Harcourt reaches out, and the figure grabs both of her wrists, starts to pull, but I sweep the falchion down and sever both of its arms, then strike it in the face. The head dissolves in dust and the body falls backward.

The other figures lurch forward. I grab Mrs. Harcourt’s hand again and pull her back toward the main street.

“That wasn’t him!” I say as we run. “That can’t have been him.”

Tears streaked the dust on her face.

“I know that,” she says. “I know you must be right…”

On either side of us, walls crumble as arms reach for us. I think we’re heading back the way we entered the city. The line of arms blocking the street is gone, and there’s just a shallow trench, which we cross in one step, but the pavement is churning further ahead.

I don’t want to stop. I keep my grip on Mrs. Harcourt’s hand.

Another full figure pushes from the street, straightening to full height, dust settling around her.

This brings me to a sudden halt. Mrs. Harcourt stumbles but doesn’t fall.

My mother has come out of the ground. A grey statue of my mother, but the details are clear. The flower, the mountain star, is in her hair, just as I remember it.

Was she wearing that on her last expedition to the City?

“Sam,” she says, and it’s her voice.

“No,” is my reply, because I know it’s not real. It can’t be real. But now I’m filled with doubt, and I know why Mrs. Harcourt reacted the way she did. When she saw her husband.

“I felt you here,” my mother says. “We felt your arrival.”

Maybe it is her. Maybe the City absorbs people, makes them part of itself, uses them up to create this shield, whatever the magicians were trying to do. Maybe that’s why the City vanishes. That’s its protection.

“Lucky, you know it’s not her,” Mrs. Harcourt tells me.

“Are you really my mother?” I ask and wonder why I allow these words to come out of my mouth. Even if this is my mother, she’s changed. She’ll pull me under, make me like her.

What if I take her with me?

She’s beckoning. Other figures are coming out of the walls on either side of us, and there isn’t any time left. The City’s going to disappear again any minute. We have to get out of here.

I grab my mother’s hand and pull her toward me with some force. I don’t look at her, just turn away and keep tugging, and it’s like dragging something through the mud. There’s a sound like boulders falling. She struggles, trying to break away, and then her hand comes off in mine, breaking at the wrist.

I reach back and grab at her hair, take hold of the mountain star.

It breaks off.

She claws at me. Her face changes, becoming someone else. I recognize the face but can’t place it, and it changes again, becomes Gerard, and I now know that this thing was never my mother, but some kind of lure. This thing, I realize with a rush of horror, like a punch to my gut, was probably why my mother and Mr. Harcourt never made it out, never even got back to the treasure vault.

With a burst of rage-fueled strength, I bring my falchion down on the head of the thing that looks like Gerard, cleaving it into two large chunks. The headless figure drops away and smashes into bits on the cobbles.

Arms are coming up out of the ground all around us, and Mrs. Harcourt is swinging her rifle like a club. I flail around me with the falchion. I just want to escape now.

Mrs. Harcourt is free and clear.

“Come on!” she cries.

We run. The neighborhood we first encountered, the low houses with the little yards, is ahead.

We make it through the houses and now we’re climbing into the hills, getting closer to the mouth of our secret pass. I chance a look behind us.

The City is gone.

I drop to my knees, gasping for breath. Sweat springs out on my brow, and I feel sick and have to close my eyes, to breathe. I feel a hand on my back. Mrs. Harcourt.

When I open my eyes, the sickness having passed, I’m looking down into the bare valley, the grass rippling in the light breeze.

“We made it out just in time,” Mrs. Harcourt says. She’s sitting on a boulder a few feet away, and she’s covered in dust.

The falchion is on the ground at my feet, but I’m clutching something else in my hand, holding it tight. I look and see it’s the mountain star, made of stone. I rub it with my thumb, and it remains intact, doesn’t crumble.

“We lost Gerard,” Mrs. Harcourt continues. “Lost the mules and the drivers. Another expedition and worse than nothing to show for it.”

Her voice cracks, she puts her head in her hands and her shoulders heave with quiet sobs.

I want to tell her that at least we learned something, that the City has more dangers and mysteries than we thought, but I can’t say that now, not so soon after the loss of our old friend and companions. I put the mountain star in my pocket, next to my lucky coin. Then I take the coin out, roll it between my fingers. I don’t have any particular decision to make, but the coin’s weight is reassuring, even if I don’t feel very lucky.

“Heads,” I say, “nothing to show. Tails, well…”

I flip the coin, catch it and slap it down on my forearm.

Tails.

I hear the characteristic thump of hooves on rocky turf. From out of the pass comes one of the mules, laden with loot chests. The mule stops, crops some grass and chews it, thoughtfully, as it stares at me.

— ♦♦♦ —

END

Next Week:

Thirty Days Hath October By Stephen Woodworth, Art by Bradley K. McDevitt

Thirty Days Hath October By Stephen Woodworth, Art by Bradley K. McDevitt

Ryland shed his coat and tie and stretched out on the couch normally reserved for witnesses waiting to be interrogated. “Happy Hallow—”

“Don’t,” I snapped. “As far as you’re concerned, it’s November 1st.”

But the charade was useless. The calendar date did not fool the Old Gods. They knew perfectly well what day it was.