Story by Coy Hall

Illustration by Tim Soekkha

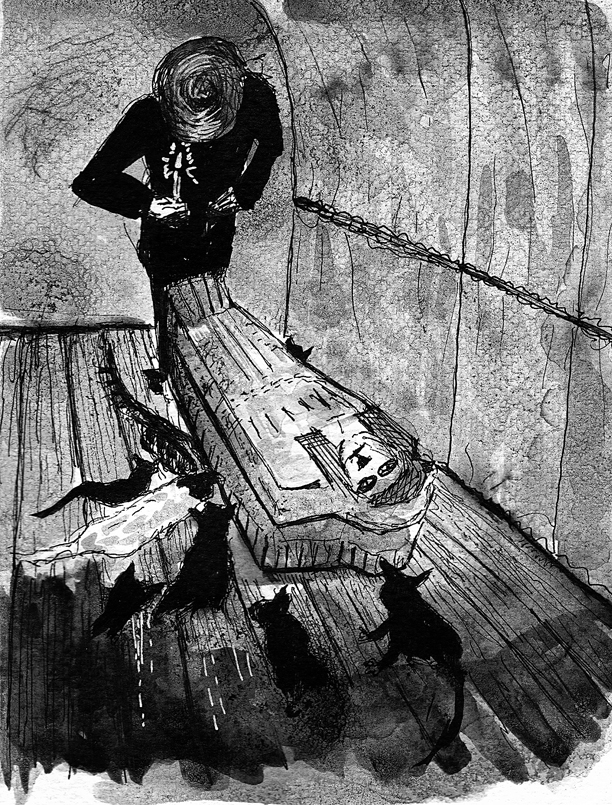

Nelson Henry, formerly of Her Majesty’s Royal Navy, formerly of Egypt, walked alongside the creaking wagon. Beneath his cap, a pair of dark eyes, proud and distrustful, remained vigil. Sweat gathered in the lines of his sand-weathered face. A lifelong traveler, he was accustomed to long stints without beds and houses, though age made the discomfort more irritable. Henry had the look of a man who’d begun life in poverty, gained a fortune, and then lost it again, a man stretched to a gossamer-thin joint by toils. He’d led several lives in his fifty-nine years.

Since disembarking in San Francisco, he hadn’t let the coffin box and its precious contents out of sight. Henry had suffered highwaymen before, he claimed (in a Yorkshire accent the men mocked), the talented thieves of Egypt and Asia Minor. He’d had more precious, better-guarded cargo than this coffin snatched from his possession. Being a man of experience, he carried a fine old six-shot in the pocket of his coat.

He’d remain guarded until he ended the journey, some hundred miles inland from the Pacific coast – a journey that had begun in Egypt, crossed the sea to Indochina, and crossed the vast Pacific. For every mile of the thousands he’d traveled, he watched the coffin, looking upon Ahmose’s face only once since the night she’d been kept in his hovel. That was the night he’d learned to distrust her, the night he’d noticed the first alteration in her appearance. Although the men had asked, he would not allow them to look either, not until Ahmose reached her new owner, Mr. Donovan. He didn’t want rumor to soil his chances of receiving substantial pay.

Ahead, with day waning over the cedars, the boss, Eli, stopped the caravan with an uplifted hand. Inwardly, Nelson Henry groaned. Although prepared for trouble, he was anxious to avoid any difficulty. He moved to the front of the wagon, patting a horse he’d declined to ride. The foremost rider, the caravan scout named Lee, had returned through the trees, his horse silent against a bed of needles. A seedy little man with a taste for knives, the scout possessed a shadowed face. When he approached, he looked around at the party of six and said, “It’s the bunch that camped out at Donovan’s before we left. The settler family with the kids and old folks. The bunch from Illinois.”

A wave of dread, palpable, passed through the ranch hands. The horses absorbed the tension and, disliking the change of air, stirred, clipping their shoes against the rocky soil. Henry, too, felt anxious, but it was more than the threat of violence that troubled him. Something ghastly had occurred. His thoughts went to the coffin in the wagon, the box containing a girl he’d smuggled from the desert. The last time Ahmose had undergone physical change was in the presence of bloodshed. He feared what bringing her into such an atmosphere would do. Superstitiously, he thought, grim things happen around her. She draws them near, attracts them. He corrected himself with sobriety. This is fantastic. Only lesser men would believe it so.

“Say, what is this?” Henry asked, stepping from the wagon. “It isn’t,” he struggled with the colloquialism, “injuns, is it?”

Lee, the scout, watched Henry, as he would ponder a fly on his lunch. “Indians, my ass,” he said. “Pap, the only injuns ‘round here sell blankets on the road into town.” The scout swiveled until the horse beneath him blocked Henry from view with its immense hindquarters. He then looked to the boss, a man twice his age and twice his size. “Where’d that joker come from anyhow?” he asked.

“Forget him. What happened?”

Lee tried to conquer his emotions, but he was clearly shaken. Distractedly, he said, “They buried ‘em partially under a fallen tree. I’d guess it was jokers sellin’ highway protection. Those folks had a feather bed with ‘em.” He pulled clumps of feathers, gray-white-brown, from his satchel and threw them to the wind. They fluttered back to the pines. “Whoever did it had a good time. They tore up the bed and scattered it for a quarter mile. Looks like snow when you first catch glimpse of it.”

“The folks?”

“Big cats dragged ‘em out’d be my guess. They’re just bone and sinew now. I chased off some pissy vultures. What do you say?”

Eli considered. After a moment, he addressed a rider at the back of the impromptu council. “Bourne, ride back into town and get the deputy marshal out here. Make haste.” At the order, the rider spurred his mare and began to retrace the road into the pine forest. “Rest of us are gonna have to dig a pit and bury ‘em. Mr. Henry, get off your feet and up into the wagon. No more slow crawling.”

Frightened, Nelson asked, “What about Ahmose? Mr. Donovan, your employer, he wouldn’t want her to—”

“—Would you stop callin’ it that?” Eli spat a wad of tobacco juice, spotting the thigh of his horse. “Damn you, it’s a dried up corpse. It ain’t got a name.”

“Everyone has a name,” Henry grumbled.

“Bullshit. Go get in the wagon.”

Obediently, the man Victoria had nearly knighted, the man who, before disgrace, had given orders rather than received them, moved to the back of the wagon. He would ride with the coffin, constructed like a chest of guns, under his watch. Tales of marauding Indians didn’t seem so fantastic in the wilderness, but maybe Lee was right, maybe there were worse things. It’s you, he thought, imagining Ahmose’s feline face. You’re pulling them in, aren’t you? He felt a sliver of guilt. I should’ve dropped in the sea.

The coffin box shifted as the wagon started forward, bumping over rocks. The uneven ground reminded Henry of seasickness, and at that he wondered if he could really make a life here, in a country so far away from everything he knew. Damn them, he thought, recalling not Eli and his ranch hands, but the face, the tone of Colonel Braddock in Egypt as the hypocrite made his verdict clear. If Henry hadn’t fled the country, or anywhere else in Her Majesty’s empire, he’d be in prison now, a scapegoat for men of better breeding, men like Braddock with titles and commissions.

Voices penetrated the canvas walls. As Lee speculated on whereabouts, Eli told the cowhands to load their weapons. Holding to precious Ahmose, perfectly preserved save for a tear on her leg, a specimen of incredible value, a mummy that Braddock would’ve taken to London to win acclaim, Henry fetched the six-shot from his coat. A deep depression came over him.

The urge was there, too, to loosen the nails and gaze upon her cat-like face. He had to know. He had to see.

— ♦♦♦ —

He’d fallen against the door, closing off the hovel from the wind and cutting sand. As his heart convulsed, he kicked away the scrawny felines clamoring for food at his heels. Outside, wind battered the walls and whistled in the fissures. Looking down at the cats, pondering their skin-draped bones and the visible ridges of their spines, he wondered how they’d survived so long. Not only had they survived, it seemed they’d multiplied in his absence. He hated to fathom what graveyard carrion kept them going. Damned jackals they were. Again he kicked them away, and their whines became angry wails.

With a brush of his arm, Henry cleared the room’s single table. A gust sent a tremble through the front door, but he’d spent enough nights here to know he was safe. The hovel would be half-buried in the morning, but it would stand abuse. Fighting the cats for space, he went to work lighting candles of fat, cutting away the darkness. Satisfied, he found a water skin and drank until the mud in his throat cleared. The cats yowled jealously.

Outside the door, a heavy form thudded against the planks with urgency, and quaked the multitude of candlewicks. Shadows moved. Nelson Henry waded through the cats, stopping at the door. A mounting pile of sand had amassed at the threshold; grain by grain, it infiltrated through the cracks. Again the thud, rippling the old planks. A muffled voice. He wondered if the boy outside would die if left stranded. Would he return to the village and lose his way? Would he suffocate as sand filled his lungs?

Morbidly, Henry thought of hourglasses, of time running low. This was his time to stop, the last bend in the river. If he opened the door, he had to move forward.

When he unlatched the entrance, the boy threw himself inside. Henry put his shoulder to the door, shutting away the windstorm again. He looked at the boy without pity. Doubled at the waist, the child brushed sand from his dark hair and wiped at his eyes. He coughed out the infernal sand, expelling it from his mouth and throat. Despite his youth, he wore the tattoo of a local carnival troupe on his forearm. Even the sand had not blasted it from his skin. He was a known criminal, a talented pickpocket.

Wary of the intruder, the cats retreated to a shadowy corner of the hovel.

Henry eyed the boy. “When I leave tonight,” he said, “I want you to poison them.” He made a gesture towards the shifting cats.

The boy nodded, still too battered to speak. Nelson offered the water skin and the boy took it greedily. As candlelight danced over his dark features, he drank to his satisfaction. “It’s buried in the crates,” he said in his native tongue, his chest heaving. Moving through a sandstorm could make even the hardest of men see death, and the boy had that look in his eyes. “There was a problem with the resin. One of the legs had become glued to the floor. We had to rip it free.”

Nelson grimaced. Given time, he would’ve freed Ahmose with little damage. She deserved gentle care. Her flesh had remained intact for three millennia, only to be desecrated tonight by grave robbers. He could only ask, “How much damage?”

“Ripped off part of her left thigh.” The boy demonstrated the length with his hands, about a decimeter. Having less love for the cats than even Henry, the boy stomped viciously at a pair of blues. They were young, virgin to the boy’s cruel demeanor. “The cats,” he asked, “where do they come from?”

“I don’t know,” Henry admitted. “They began to gather here after we uncovered Ahmose. I can’t rid myself of the pests.”

“The colonel is with his whores.”

“Excellent,” Henry said, busying himself with the final preparations for what would be an end and a beginning, moving swiftly about the crowded hovel.

— ♦♦♦ —

To Nelson Henry’s relief, there would be no gunfight with highwaymen. Presumably, the murderers had moved on with whatever loot they’d acquired. “That isn’t the way they do,” one of the hands informed him. “They have no interest in fighting men on horseback with guns.”

“No profit in it,” Henry observed.

The young man nodded. He held an unlit cigarette between his lips. “Me, I’d worry about those greedy panthers if they’re still around. They may be on the prowl when we sleep tonight. The tang won’t go from the air even when we bury those folks.”

Cats, Henry thought abysmally. Damn cats again. Felines, it seemed, traveled with Ahmose. Her mere presence attracted them. He’d even caught a tom sleeping atop her coffin box during the Pacific voyage. Sickened, he’d brutalized the tabby only to find it in place again the next morning. He recalled the cat motif of Ahmose’s tomb as well – the princess surrounded herself with cats in life as well as death.

It was not without fear that Henry remembered the boy in the village, his cracked skull spilling onto the hovel floor, the hungry strays lapping gray fluid and blood. It was an image burned in his memory. Panthers, he thought, would feed more heartily than strays.

Amongst the men, dread intensified as the caravan passed from the pine grove into an area of younger, scragglier trees. The feathers, stuck in the limbs and lining the earth liken fallen leaves, were the first ominous sign that they approached the site Lee described. The inarticulate scout had been correct in his account. Where the feather bed had been torn and its contents scattered, the tableaux looked like one of snow. The sight of a mundane bed ripped apart, a possession of a husband and wife important enough to haul across the country, made Henry ill.

The wagon rolled to a stop. After tapping the coffin box reassuringly, Henry rose from his kneeling stance. He couldn’t bring himself to pocket his gun. He held the weapon as he emerged from beneath the canvas. Up front, the riders gathered around the foreman and scout. There was a raw smell in the air, more pungent than horseflesh.

“Dig out a shovel from the supply wagon,” the foreman ordered.

The men dismounted, joining Henry on the ground. “Lord God have mercy,” one of them said.

Panthers had dragged raw bodies fairly close to the road.

“And one of y’all need to fetch a rifle. Be on watch for one of those cat beasts down from the mountain.” Eli grimaced. “Looks like they filled their bellies to content though.”

Eager to put the bodies under while light remained; the men and horses fell away, leaving Henry to look upon the scene. Steeling himself, he swallowed trepidation and gazed about. The skeleton of a wagon, stripped of valuables, stood cockeyed and broken at the edge of the road. There were a couple lumps of flesh in the back; children, Henry guessed. A feast of flies now, covered in black. The buzzing made for awful racket. Off to the right of the trail, lying close to a fallen tree burdened with moss and full of dark rot, was the remainder of corpses, having been pulled from their tucked-away positions under the log. A blanket of flies there, too. In the distance, where the road turned, there was another wagon husk, this one with a wheel missing and another wheel that resembled a broken jaw.

“Just dig a pit,” the foreman ordered.

Henry approached Eli. Even when they were both on foot, he had to glance upward to look the man in the eye. A craggy, wide face behind a graying beard, Eli was what Henry had imagined Americans to look like, indestructible, hardy, and stubborn. “Are the cats very numerous here?” he asked.

Eli shrugged. “Paddy, go find some water,” he ordered. One of the men went to the wagon. Eli caught Henry watching the man distrustfully. “Say, Pap, tell me somethin’. About how much is Mr. Donovan givin’ you for that mummy? You eye it like it’s wrapped in gold.”

“A handsome sum,” Nelson replied. Behind him, the first clink of a shovel echoed through the trees.

“We’re damned lucky the highwaymen don’t know that.” He paused. “You know, I saw Mr. Donovan’s collection once. He says it’s a cabinet of curiosities. Weird as a carnival. He invites folks over to look at it. A Nevada senator came to look at it once. It’s a whole room. Got stuff suspended from the ceiling.”

“Is that so?”

Eli nodded. He spat.

“What about the cats?”

Again, Eli shrugged. “Unlikely they’d bother us with so many about. ‘Sides, like I said, they got full bellies.” With that, he turned and went amongst the men. He picked two more from the group. “Get up ahead and set a camp while there’s light,” he ordered. “We’ll meet you when this is through. Take the wagon and let Mr. Henry accompany his girl. He won’t be no use diggin’.” Possessing a barometer for the temperaments of his fellows, he added, “Remember that Mr. Henry’s a guest of Mr. Donovan.”

— ♦♦♦ —

With another tangle of limbs added to the fire, light spread over the wagon wheel and up the canvas. Flames crackled. Smoke snaked upward into the trees, escaping the limbs and dissipating above where moonlight was less veiled. As it had each night, damp cold descended and covered the land. Despite aversion to his escorts, Henry huddled with the uncultured brutes in the shifting halo of light. The persistent image of the settlers had kept him from eating. A sense of anticipation troubled him, and he was cold.

Reassuringly, the foreman said, “Should hit Donovan’s by tomorrow night.” With that, he handed a jug of whiskey, what the men called moonshine, to Henry. The liquor had a mordant bite, and after a couple drinks it numbed Henry’s tongue. With an empty stomach, the liquor went to his blood immediately. He felt the drunkenness first in his vision, which slid a little, like a loose skin had been applied to the world. He took another drink when the jug came full circle. It’d been a couple months since he’d had quality liquor. It felt good – and the more he drank the less he thought of the innocent settlers and their children. The less he thought of Ahmose. His glad participation made the ranch hands loosen up a bit. For a while, they talked of the highwaymen, of Donovan, of San Francisco, of women. It was when the jug had passed five times that one of the men asked about Henry’s cargo. “Is that thing really from Egypt? You ain’t a con, are you? Be level.”

Henry squirmed a little. Interrogation in any form made him uneasy, especially with criminal charges on his shoulders. He was desperate to appear as unlike a crook as possible, but the moonshine made pretense difficult. Faced with anticipatory stares, base pride won out. He found himself wanting to impress the dirt-caked heathens.

“Indeed, she is,” he started. “Right from the very sand of the pharaohs. Mother England won’t let them out when they’re complete like her. Ahmose, about twenty-five centuries ago, was the daughter of a pharaoh. She was buried with all the finery you’d expect, though the gold was looted millennia ago.”

“How’d you get her out?” Lee asked.

Henry laughed. He considered stopping but he couldn’t resist. He told them of the pickpocket child, of Colonel Braddock, of the excavation site and his hovel near it; of the port in Alexandria where the Mediterranean offered freedom. He told them nothing of murder – he wasn’t that foolish. He told the nothing of cats.

“Why’d you do it? Can’t go back now, can you?”

“To retire to this beautiful country,” he lied. “Now, if you gentlemen will excuse me, I need to relieve myself.”

“Sure, Pap,” Eli said. He laughed. “We’ll keep the jug warm for you.”

With an aching bladder, Henry gathered his faculties and moved towards the shadows at the far edge of the wagon. The voices over his shoulder provided stark contrast to the still forest beyond the light. The moon penetrated to the floor in shafts there, bathing the treetops.

Before returning to the fire, he decided to check Ahmose. At night, a drawn flap covered the rear of the wagon, a device to aid sleep and discourage curious wildlife. When Henry approached, he found the flap untacked, quivering from a breath of wind out of the woods. The cold breeze went straight to his core. Just as suddenly, he felt anger. Had the men been prying? Had they come back here without his permission? Is that why they’d drugged his mind with liquor?

He lifted the flap and peered into the darkness. There was a gamey stench in the air – the smell of breath from a belly full of meat. Atop the coffin, two yellow eyes, faintly luminescent, opened. A rumble of distrust moved in the predator’s throat, an eerie, muffled hiss. A mouth opened, revealing teeth. The animal stirred in the darkness. Claws scraped wood. The panther’s face, reddish-yellow, emerged, like bas-relief in shadow. Henry threw the flap closed and stumbled backward. His only urge was primitive: fear animated his drunken body, and he ran to the firelight.

“Get the guns,” he shouted. “There’s a damned bloody panther by the wagon.”

Eli lifted a rifle from the ground. The other men, not so lucid, hesitated, looking uncertainly into the darkness. Henry fumbled through the pockets of his coat, finally locating the six-shot. He turned with the gun in his grip, just in time to see a flash of fur, a rear paw pressing the dirt. Alarmed, the panther fled toward the trees. Eli’s rifle boomed, an explosion that unsettled every bone in Henry’s body. Impressively, the foreman’s aim was true. The bullet shattered the panther’s hip, turning the cat in a half circle before it hit the ground. Pathetically, the beast raged and hissed, bearing its massive teeth. The bullet, however, had effectively crippled the animal. The cat could only drag itself towards the fire, which it did, a quake like a purr in its chest. Eli had the rifle at his shoulder again. Now the other men, armed, joined him. Several fired into the body of the panther, although Henry was not among them. With Ahmose in his thoughts, he couldn’t bring himself to shoot. Riddled, the cat expired in the dirt, its head and chest bloody pulp. It had been a striking animal, three feet tall and six feet long, with a lengthy tail and thick paws. Its underbelly was light and tawny.

The scout approached the cat first, whistling as he drew near. “I’d say that’s a two hundred pounder. A little close for your taste, huh, Pap?”

“Damn good shot,” Henry breathed. Unwelcome memories gathered. Again, he thought of Ahmose, of the inscriptions on her tomb walls, of how her face had shifted that night in the hovel. The shot had to be taken, he reasoned. No doubt the jackal still had flesh from the settlers in its ample belly.

“You say that thing was by the wagon?” Eli asked. His hands were trembling. His throat moved when he swallowed.

“Inside the wagon,” Henry corrected. “Atop the coffin box.” Guarding Ahmose, he thought, just like the rat-catching tom on the freighter. Just like the hovel strays. Just like the art on the walls of her tomb. What made the cats more than coincidence? Three occurrences? Four? How many times?

Averting his eyes, he moved from the dead, open-mouthed panther and checked the wagon. The nails in the coffin had not been disturbed. Desperately, he wanted to get the cargo to Donovan, to free himself of the burden. How much, he wondered, would the dead panther alter her appearance?

— ♦♦♦ —

It was still dark when he and the pickpocket, dragging the crate atop a sled, again reached the hovel. Although the sandstorm had abated, mounds had been left behind, including one that reached four feet high and barricaded the front door. Dropping their ropes, listening for any sign of approach over their shoulders, he and the boy dug out the entrance with their hands. Protected only by the night, Henry feared that somehow Braddock would learn of their thievery and send men with guns. But, as they cleared the sand, no riders approached on the horizon. The post-storm hush was peaceful and still.

With the door cleared, he and the boy lifted the crate from the sled and over the threshold. They kicked away the clamoring strays and placed the oblong box on the floor. In the corner, a few candles still burned at the base. The others were cool stumps. The urge to open the box and look upon Ahmose seized Nelson. He had to see her again, if only to assess the damage. Without a word, he snatched a crowbar from the table. He motioned for the boy to keep the crate from shifting as he pried.

In his native tongue, the child said, “Now we discuss my fee.”

“You already received your fee,” Henry replied, a bit of the naval officer returning to his tone. Threateningly, he gripped the crowbar. He would not tolerate insolence. He’d brain the child if necessary, and leave the savage here for strays to devour.

“How much will you sell it for?”

Henry bristled. “There are two bidders waiting. I don’t yet know how much.”

“You have an idea. You will be a rich man, no?”

“Certainly not.” This will buy a new start, Henry thought, but how could he explain that to a child filled with want and fancy? A child to whom a palm of copper constituted a full day’s work? The pickpocket couldn’t fathom wealth.

“Maybe I’ll go see Braddock. Maybe then you’ll give more of a share.”

“Open the box. We’ll see what shape you left her in and then we’ll talk.” Frustrated, Henry swung the crowbar at a tom that slinked against his boot. The iron caught the spine, breaking bone with an unpleasant crunch. The cat lurched onto its side, yowling in pain. At the outburst, the other felines gave clearance. Henry gripped the crowbar and put the tom out of its misery. The head caved like a broken gourd.

The boy watched, his eyes growing wide. Obviously, he hadn’t expected the old man to be capable of violence. Armed with nothing but a knife in his clothes, the child grew wary. Obediently, he secured the crate. Nelson, after kicking away the animal, went to prying. The nails lifted from their loose holes without strain and, in seconds, the lid was free. Henry stepped back and grabbed one of the candle stubs, still alight. He brought the flame forward and looked over the ancient princess. The cadaver was black and gray, shriveled to bones at her legs and arms. The stomach dipped flat beneath the ribs. The face, however, and the coarse black hair on the skull were preserved magnificently. It was breathtaking to look at Ahmose. In her clear features, the cheekbones, the mouth, the tempered brow, the beauty of her living face remained evident. Jewels, sewn into bandages on her arms and neck, dulled finery the grave robbers had missed or ignored in superstition, only heightened her beauty. In many ways, it looked as though Ahmose had only lain down to a thousand-year sleep.

As he studied the face, the cat motif so prevalent in her tomb made more sense. The odd consistency of cat-headed, anthropomorphic figures like Bastet and Sekhmet on the rock walls had been something of a mystery. The sheer preponderance was unusual. Looking at her in the glare of the candle, though, his intellect opened to other possibilities. There was something feline in the lines of her face, a trace of the predatory cat. It was more than mere resemblance. This, he thought, feeling a bit overwhelmed, would have been a goddess in the flesh to her people, a walking deity. The ancient world had a capricious way of approaching bodily deformities. Ahmose looked like an avatar of Bastet, the cat-headed goddess. Her people would’ve regarded the likeness with awe. How, he wondered; had he not seen the resemblance before?

One of the strays leapt onto the edge of the box and peered down curiously.

Henry addressed the boy sternly. “Was her face different?” he asked. Now he doubted. He could not have missed the visage before. The face had changed. “Did it change from when you secured it?”

“I cannot be certain.” The boy’s face was bloodless.

“You’re certain.”

The boy was silent.

“Damn it, you’re certain! Tell me! Did it change?”

The boy nodded. It had changed.

In another moment, two more cats had graced the rim of Ahmose’s coffin. The other animals looked up at the crate expectantly. With the crowbar in hand, he struck another tom on the floor, breaking open the skull. It was an experiment he wouldn’t forget. As the feline expired, lines in Ahmose’s gaunt face shifted, drawing inward, pinching, subtle and fluid as a breath across a palm of water. He killed another cat, and again Ahmose changed, as if she absorbed the very spirit of the animals.

It can’t be, he thought. “Cover her up,” he ordered. “Secure the lid.”

The boy hesitated. “My fee,” he muttered.

Henry gripped the crowbar until his knuckles whitened.

— ♦♦♦ —

“It’ll be safer by the fire,” Eli said. “You’ll be alone if you sleep in the wagon.”

“There’ll be a sentry,” Henry said. “At the first hint I’ll join you.” He brandished his six-shot. “And I’ll keep this near.”

Eli didn’t persist, shrugging it off as an old man’s stupidity. The goodwill of drunkenness had fled the group completely. The men were tired and nervous and resentful. They lay in the firelight as Eli, rifle perched on his lap, took the first watch.

More than a desire to keep watch over his cargo separated Henry from the group. He’d decided to retire to the wagon for a reason not so easily explained. As he had several times before, he felt seized with the urge to open the box and ascertain the changes in Ahmose’s face. When the panther died, to what degree had Ahmose changed? Dangerous curiosity moved him towards the back of the wagon. Not without trepidation, he lifted the flap. For a moment he stood looking into the darkness, his eyes, full of firelight, adjusting. Only when satisfied that another large cat had not invaded the space did he pull himself up and inside. Residue of the panther remained as a gamey stench. Henry wondered if the animal had urinated – the odor resembled piss.

On his knees, he observed the coffin lid.

The nails were loose. The lid had been lifted and replaced clumsily. He grew ill. Had one of the men come here without his knowledge? He wondered how or when. Henry groped in the darkness for a crowbar he’d stashed in the supplies. The tool was where he’d left it, which surprised him. He gripped and lifted the lid. The coffin was empty. He nearly cried out.

In the far corner of the wagon, the crick of tussled bones caught his ear. Something moved in the darkness, something huddled in the mound of supplies. A face similar to that of the panther became evident, although there was uncanny humanity in the features, in the texture of the dark hair. It was shape alone, no bristling red-yellow fur, no hiss in the throat. Ahmose’s gaunt skull, covered in resin-rotted bandages, had further distorted its shape. The brittle cadaver put hands to the plank floor and shifted forward.

For Nelson Henry, a rip appeared in the fabric of his thoughts. He found, where there had not been before, an ancient memory. The vision absorbed him. He saw a young girl in a world he knew only by its ruins, a girl lost in a smoke-veiled ceremony, a girl treading in the holy of holies. A statue of Bastet became apparent, emerging from the darkness. Then there were priests, angry, threatening the girl in curses.

He could not scream for Eli and the men, although his throat pulsed with the effort. He could not lift himself and hurdle from the wagon – here, too, the effort was impotent. He could not even shut away the horror by closing his eyes. He had to see. The mummified remains, animated to primitive movements, struggled across the divide. A mouth, sharp and hard as a panther fang, touched his skin. Then Henry was millennia in the past, a voyeur hidden by the veil of incense. Quietly, Ahmose ate his throat.

— ♦♦♦ —

END

Next Week:

A Pittsburgh Left. By Michael McGlade, Art by Jihane Mossalim

A Pittsburgh Left. By Michael McGlade, Art by Jihane Mossalim

She wasn’t just any dame; she was one of the best PI’s. Isabelle Shaw listened to the mousy man in the diner. He was supposed to be a new client. The story he was weaving was making her have second thoughts. It reeked of conspiracy theory nonsense. But when her client shows up dead of an apparent suicide, she reconsiders and is hot on the trail of the truth.