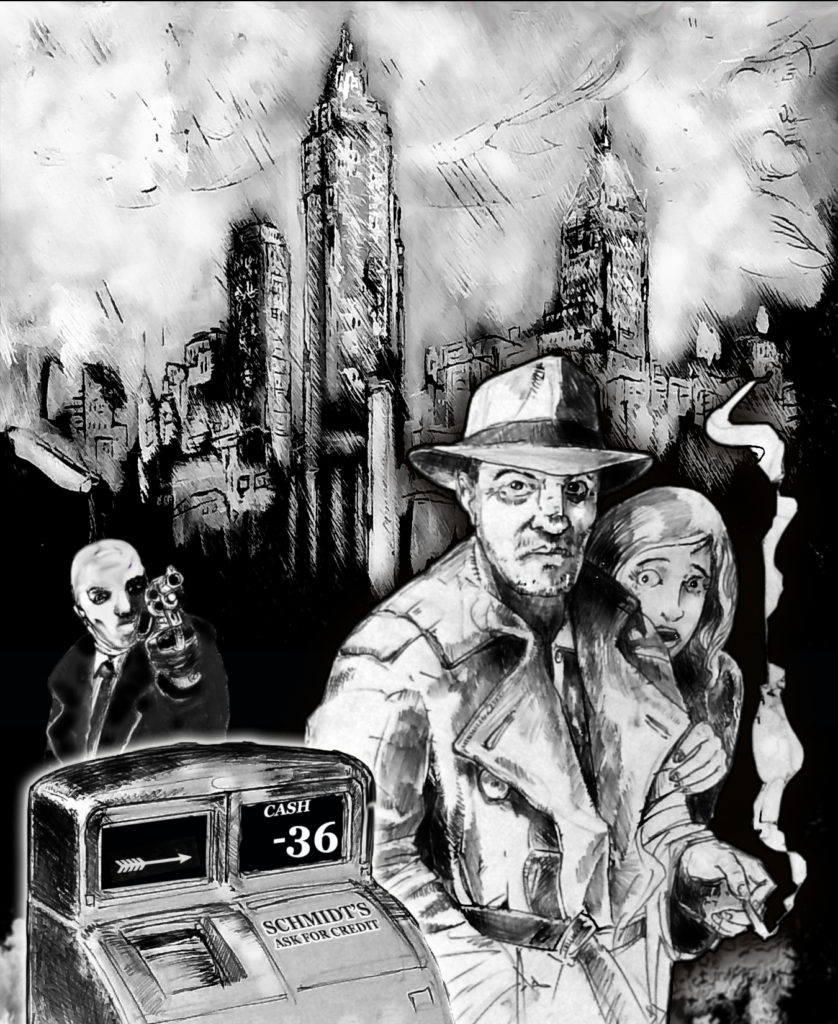

Story by Fraser Sherman / Illustrated by Toe Ken

New York, 1937

I walked a half-mile in the rain to Sammy Schmidt’s deli because I wanted a hot pastrami on rye, and I couldn’t afford to pay.

If there’s one thing the past two thousand years have taught me, it’s that you don’t always get what you want.

“Sammy?” The bell on the deli door rang as I stepped inside, rain dripping off my trenchcoat onto the linoleum. “I was wondering if you could stake me again—”

The sentence died unfinished. Sammy lay behind the deli counter with bullet holes in his heart and his head and blood congealing on the walls, the cash register and the sandwich sitting on the counter. The register’s till jutted open; his last act had been to ring up a 36 cent purchase.

I cursed a blue streak as I strode to the phone and called the cops. Sammy had been one of the best guys I knew in New York, though probably the city’s worst businessman. With the handouts and free meals he provided bums and neighbors down on their luck—like me—he never had more than five bucks in the register or the bank at a time.

And some lousy bastard had killed him for so little. For money Sammy would probably have given the killer with a smile, if he’d asked. But the world’s full of lousy bastards. It always has been. “ … Yeah, sergeant, that’s the address. No, I didn’t touch anything but the phone … Fine. My name’s Al Soares.”

I hung up, wondering if I should have walked away without giving my name. A lot of cops don’t like me.

Of course, most people don’t like me. I’m kind of tired of them, too.

I looked back at Sammy’s corpse and sighed. Sure, Sammy had been a real mensch, but I’d known hundreds of guys—okay, dozens—as good as he was. Several of them had died stupid, pointless deaths. Being a swell guy was no protection against anything.

There was only one set of muddy footprints on the floor beside mine. That would be the signal for Nick Carter or Sam Spade to start hunting their friend’s killer, but Sammy wasn’t my friend, not really. Besides, the rain would already have washed away the trail.

As my eyes followed the killer’s path up to the counter, I thought of Rebecca Schmidt, Sammy’s kid. She’d be at the temple tonight, chairing a fund-raiser for German refugees. I guess I’d have to go and break the news to her. I didn’t particularly want to, but—hell, I owed Sammy for two or three dozen hot meals, better someone Rebecca knew than a cop. I started thinking of how I’d say it … and then I saw the footprints ended at the carpet behind the counter, where the stairs up to the Schmidt’s tiny apartment began. I didn’t see them go out to the door.

Surely the killer couldn’t still be up there?

I headed up the stairs and took a look around. Like the joke goes, the rooms were so small, even the mice were hunchbacked; it only took a few seconds to see nobody was hiding there. I’d been a chump; the dirt on the killer’s shoes must have rubbed off on the carpet before he left.

The funny thing was, the Schmidts’ rooms were neat as a pin. Didn’t look like he’d searched for money or anything else.

So why’d he bother going upstairs?

— ♦♦♦ —

“A Jew who gives away money?” Det. Matt Kearney, a six-two slab of beef who wasn’t as dumb as he looked, struck a kitchen match on the windowsill and applied it to his cigarette. “Ain’t that a whaddyacall it, sacrilege for kikes?”

“He did more than give away money.” If Kearney hoped to get a rise out of me, he was wasting his breath. I remembered when they accused us of baking our bread with children’s blood. “Remember that tenement fire a couple of months ago? Sammy rushed in, pulled out three spade kids he didn’t even know, almost got himself killed doing it.”

As Kearney digested that, I glanced at the men carrying Sammy’s body out into the rain. “Your guys find any clues, Kearney?”

“Clues.” He said it like a four-letter word. “Crimes like this you don’t find clues. You just hope a witness can ID the guy, or a stoolie gives you a tip. Thirty-six cent robberies don’t come with clues.” His eyes narrowed suddenly. “Don’t try pulling a con like you did last time.”

“Don’t worry, this is nothing like the LaGuardia case.” Like most of the boys in blue, he didn’t believe I’d stopped a dybbuk from possessing Mayor LaGuardia. “Just one stupid robbery.”

I’d pointed out the footsteps going upstairs; Kearney figured the hood had lost his nerve or realized the Schmidts weren’t going to have anything worth stealing, which made sense. “I’m gonna go see Rebecca,” I told him, “unless you need anything else?”

“Don’t need nothing from you—ahh, I suppose you’d better tell the girl to come to the station tomorrow, we’ll take a statement. I’d go and get one but—” He gestured at the rain. “And it ain’t like she’ll know anything useful.”

I left the deli, still starving—I should have made myself a sandwich before the cops came—and pushed through the gawkers standing on the sidewalk under their umbrellas. I wished I had one; water had soaked through my raincoat’s loose shoulder seam into the jacket underneath. I didn’t want to walk to the temple in the rain, but I had seven bucks left to my name and no options for getting more. I could do without the taxi.

When I’d been a cobbler in Jerusalem—before a self-proclaimed Messiah cursed me to wander the world until the end of time—I’d liked rain. It refilled the Jordan, refilled our cisterns, made the crops grow.

Since then I’d spent too many rainy nights trying to find shelter. Seen too many homeless veterans, runaway slaves, desperate orphan kids struggling to do the same.

Some joker once said rain is the tears God weeps for man. Instead of crying, I wish he’d grab a handkerchief, dry his eyes and do something to help out.

— ♦♦♦ —

Even two thousand years ago, I’d done my best to avoid scenes like this.

Rebecca, a 23-year-old girl who looked six years younger, clung to my coat like a life preserver, gasping out great sobs and shedding tears that mingled with the rain already there. I put my arms awkwardly around her, trying to look like I wanted to do it.

“Rebecca.” David Mannheim, an uptown businessman I recognized from newspaper photos, tapped her on the shoulder with a well-manicured finger, but she didn’t pay attention. He tapped again. “Come home with me and Sharon tonight. You shouldn’t be alone, not with Sam gone.”

I glanced at Mannheim’s elegantly beautiful wife, standing a couple of feet behind him, smoking from an ivory holder. She didn’t seem the type to take an orphan under her wing. Still Mannheim’s offer was kind enough I upgraded him from the rich heel class.

“She’s not going to be alone.” Mrs. Kyzer, Sam’s neighbor, brushed past Mannheim, dropping ash from her cigarette on the arm of his tailored suit. “Mr. Soares and I are taking home, and we’re going to take care of her until she feels better, aren’t we Al?”

“We are?” Damn. Hadn’t I done enough?

“We can get her a doctor.” Mannheim brushed off the ash, frowning. “A sedative, yes, she needs a sedative.”

“N-no—” Rebecca lifted her small head and tried to hold back tears long enough to talk. “It’s my shop now, D-David. I’ve got to—have to—” She collapsed back against my chest while Mrs. Kyzer patted her gently on the shoulder.

I shrugged at Mannheim. He had a baffled expression, like he couldn’t comprehend someone saying no to him. Behind him, Sharon Mannheim glared through a cloud of expensive tobacco smoke like an enraged viper. So maybe Mannheim’s interest in Rebecca wasn’t fatherly? Was that why he’d kicked in a couple of grand for the fund-raiser?

But I had things to think about besides the state of the Mannheim union. With Rebecca clinging uncomfortably tight to my coat, I began the awkward process of walking her outside, with Mrs. Kyzer yammering in my other ear, demanding the gory details of Sammy’s murder.

— ♦♦♦ —

Mannheim had the right idea about the sedative. While I sat holding Rebecca, Mrs. Kyzer ran next door to her rooms and came back with some sleeping pills. Otherwise, the kid probably wouldn’t have let go of my coat until we got to the precinct tomorrow.

Once she drifted into dreamland, I whispered goodbye to Mrs. Kyzer, headed downstairs, stopped when my stomach rumbled. After a long debate with myself, I pulled a quarter out of my pocket and dropped it in the register. Stepping over the bloodstains, I went into the kitchen to make myself a sandwich. I can’t die of starvation, but I get hungry like everyone else.

I was ready to devour a thick pastrami on rye when I heard the front door scrape open. I realized that while Mrs. Kyzer had turned the sign to closed, Rebecca hadn’t locked the door. So now some schlemiel had decided to sneak in and gawk at the blood—The entrance bell hadn’t rung.

I pressed against the little window in the kitchen door in time to see there was no-one in the shop. That could mean they’d left, but when I cracked the door open, I heard footsteps close to the top of the stairs. I followed, trying to be quiet and fast at the same time.

“Get away from her—” I heard Kyzer shriek, and then a gunshot. I gave up on quiet and sprinted up. I reached Rebecca’s bedroom in time to see a killer with a silk stocking over his head shove Mrs. Kyzer’s body to the floor, then aim an automatic at Rachel’s groggy form.

I seized his arm an instant before he fired and the bullet went into the ceiling. I spun him around and gave him a shove that sent him out of the room. He banged into the stair rail, almost toppled over it, but recovered and pointed the gun at my head as I came close.

“Don’t try it Ahasueris,” he sneered. “I know your secret.”

“Well, gosh darn, I hope you don’t tell anyone.” The shot would bring cops, if I could keep him talking, this would be wrapped up in a couple of minutes. “Just kidding. Tell everyone I’m the Wandering Jew, and I’ll come see you in your nice padded room at Bellevue.” But if he knew my true name, he was no ordinary killer. “Why the hell are you after the Schmidts?”

“They’re too damn nice and help too many people. Refugees. Saving those kids from the fire. I’m more like a—a bad Samaritan.” He giggled as I took a step closer. “Know what, buddy? I don’t think your ancient curse considered what a modern automatic could do to a human skull.”

With a smug laugh, he fired into my face.

Even under the stocking, I could see his jaw drop when the pistol jammed.

I slugged him hard, slamming him against the faded wallpaper on the landing. Then I was on him, yanking the gun from his gloved hand and peeling up the stocking enough to show a fine-boned face, dark hair and a shell-shocked expression. With a sudden burst of strength, he shoved me away, snatched the gun back—but instead of firing, he broke for the stairs. “Dammit! She swore that would work!”

I followed him down the stairs, saw him race out into the rain, pulling the stocking back down. I started out after him, then stopped cold.

This wasn’t a stupid, petty robbery any more. It was murder. And he might not be the only killer.

I headed back up to the top of the stairs to wait for the cops.

— ♦♦♦ —

“The old broad’s gonna live.” Exhaling smoke, Kearney glared at me as if that was a hanging offense. “The young broad didn’t see anything clearly—”

“Why’d you bother waking her up?”

“The doc sedated her again, soon as we’d asked her.” He’d had to; Rachel had become hysterical when she learned about Mrs. Kyzer. “And all you got is that some guy you never saw before tried to kill them because Schmidt was a soft touch?”

“Doesn’t make sense to me, either.” I lit my own cigarette. Nicotine doesn’t have any effect on me—drugs never do—but if I didn’t smoke now and again, people would wonder why. Immortality is easier if you fit in.

“For all I know you put a bullet in the old broad yourself, made up the other guy.”

“Because?”

“Why’d you make up that baloney about a demon possessing LaGuardia.” His eyes narrowed. “I don’t know what your angle is, but I told you—”

“Fine. I had a clear shot at Rebecca, but instead I just waited around for my pal Kearney to show up.”

Kearney grunted and exhaled smoke.

Maybe it was just as well he didn’t believe me. Whoever the “she” was the Bad Samaritan worked for knew I was the Wandering Jew, which meant mystical or occult knowledge. Not a lot of knowledge if she thought a bullet to the head would kill me, but still, this could be more than Kearney could handle. “The Bad Samaritan mentioned the kids Sammy saved from the tenement fire, Kearney, I don’t suppose—”

“I asked a guy back at the station about it. No big deal, some Chink using a little hot plate burned the building down by mistake.” He dropped his cigarette on the floor and ground it out. “I don’t know why you keep sticking your nose into police business—” He emphasized “nose”—another Jew joke, I guess— “but don’t try to turn this into anything it’s not. I’m gonna put a couple of cops in here to keep watch, you’re going to get out of this store and go back home.” He frowned. “And where is home? We got three different addresses on you in the file.”

Damn. Police were too efficient these days. “Just outdated. I move whenever the bedbugs get too annoying.”

Kearney seemed satisfied by that, or more likely didn’t care. It’s the ‘wandering’ part of my curse: If I stay under one roof for more than three nights, bad things happen. What little money I scrape together with odd jobs goes to three or four flophouses to avoid that.

Fifteen minutes later, I plodded inside the nearest of my apartments, soaked to the skin, thinking furiously but ineffectively. A rat disappeared through a hole in the wall when I turned on the light. I slammed the door behind me, heard it hit something soft; I turned, saw a black shoe sticking between the door and the jamb.

“Ahasueris?” the shoe’s owner said. “We need to talk.”

“Howard?” I stared through the doorway, saw a familiar, dark-bearded, intense face: Howard Asher, a young, passionate Zionist and kabbalist. “Sorry, I’m not in the mood for another lecture on the Balfour Declaration.”

“It’s about the Schmidts. And the end of the world.”

“Is that some kind of metaphor?” I reluctantly opened the door. He strode inside, holding an empty meerschaum pipe, turned upside down against the rain, and I shut the door behind him. “It doesn’t make much sense otherwise.”

“This is where you live?” Whatever he had on his mind receded for a second as he stared around my pest-hole.

“Like I can afford three decent apartments? We’re in a Depression, you know. Look, I’m busy—”

“I know.” He fixed me with what he probably thought was an imposing glare. “I know about the Lame Wufniks, Ahasueris.”

“I answer to Al now, remember? And what the hell is a Wufnik?”

“Like you don’t know? You’re a legend yourself, how can you not know the legend of the Lame Ones?”

“Being a legend’s not like joining the Knights of Columbus. I don’t get together with all the other legends to play pinochle every Tuesday.” But his words nudged a bit of memory loose. “Wait—virtuous guys, beloved by God, something like that?”

“Thirty-six just souls, people who struggle and suffer, yet still find ways to make the world a better place.” His expression said this was significant. “Because they show God our potential for goodness, he stays his hand instead of raining down fire again.”

“Dollars’ll get you donuts he’ll do it anyway, sooner or later.”

“And you just can’t wait for it to happen, can you?” His expression darkened. “Raging against God because of what some false Messiah—”

“God let it happen, didn’t he?” I knew Jesus didn’t fulfill the prophecies of the Torah, so he had to be a fake—but what good did that do me? “I think I got a right to be mad.”

“Is that why you’re killing them, Al?”

“Killing who?”

“I got a telegram from the current prophet. He says you’re the key to this. The death of Sammy, the attempt on Rebecca—and all the others too.”

“What the hell? What did this telegram—and Sammy was a Lame One? He was no saint, Howard, didn’t you ever hear him tell a dirty joke?”

“Wufniks aren’t saints.” He moved close, staring into my eyes as if looking for an explanation. “Just ordinary people who do good. That’s why God loves them. People who don’t deserve what you’re doing to them.” He sighed. “Why did I think you’d come clean? Just tell us who’s working with you and once we put a stop to it … well, it won’t go too hard for you.”

“What good would it do to kill Sammy anyway? The Wufniks aren’t immortal, right? Sooner or later, they’ve got to die.”

“And new ones are chosen, sure.” Howard nodded curtly. “But for someone to kill them all in 24 hours, just to spit in God’s eye? You don’t think that might make Him mad, Aha—Al? Mad enough to end it all? Hell, we know you do.”

“You don’t know me at all.” I brushed past him and grabbed the doorknob. “Get lost. You want to spout off about me go do it at—what the hell?”

What stood outside my doorway were either two goons in cheap suits or two mountains in cheap suits. One goon reached through the doorway, set his hand on my chest and started walking forward. I found myself walking backwards and he wasn’t even exerting himself. “You should have told me you were bringing friends, Howard. I’d have bought cookies.”

“This isn’t funny, Al,” Howard said as mountain number two followed his brother in. “Meyer thought we should rough you up to find out about the killers you’re working with overseas; I’m hoping you’ll be more talkative once a couple more hours pass and your plan fails. We can protect the remaining eighteen Wufniks until then, Mannheim’s taken Rebecca to his penthouse—you’ve already failed, really, so—”

“I got nothing to say, Howard.” The goon had pushed me back to the center of the room. If I were Bulldog Drummond, it’d be part of my clever strategy. Nobody seemed worried about that. “Except I’m not involved in this. While you’re wasting time here—”

“Mannheim’s called up some guards from one of his companies. Even if there is a ‘bad Samaritan’ out there, he won’t get to Rebecca. And neither will you.”

The door slammed behind Howard a second later. I looked at the mountains. “Meyer Lansky sent you, huh?”

“He don’t like the idea of the world ending.” I wasn’t sure which of them had spoken, since neither set of lips moved. “Mr. Lansky likes the world just fine.”

Yeah, being a mob boss wouldn’t count for much at Armageddon. So I was stuck here with Lansky thugs—but why should I care? It wasn’t like Cain or the Amalekite were trying to end the world again; the Bad Samaritan’s boss clearly didn’t have enough mystical learning to pose a real threat. And when Mrs. Kyzer recovered, she could confirm I hadn’t shot her. Hopefully that would be before Lansky decided to have the mountains start breaking pieces of me off.

I still felt angry, but maybe it was just I hadn’t eaten. “Mind if I heat up some soup?”

“Fine.” One of them said. They both backed away, one to the door, one to the window, in case I tried something I guess. Both of them put a hand suggestively near the inside of their jackets; I was sure Lansky had told them to inflict flesh wounds instead of trying a fatal shot.

I took of my sodden coat, set up the little burner for my hotplate on the floor, and emptied my last can of chicken soup—my last can of anything—into a saucepan. I added water, stirred, lit the burner … and felt the anger still gnawing at my gut.

Why? Maybe because Rebecca was a Wufnik too? It made sense; who could teach a kid to be a softhearted sap better than their pop? Maybe most of the Lame Ones were a family business.

But that was a raw deal. From what little I recalled, Wufniks always get the short end of the lollipop; Rebecca would never have any more money in the register or luck in her life than Sammy had. Like the old song says, work all day, live on hay—you’ll get pie in the sky when you die. After she’d already lost her father …

That was it. That’s what was bugging me. The 36 cent sale.

I couldn’t believe it was a coincidence. Either the killer ordered 36 cents worth of something, or he’d rung it up himself, after shooting Sammy. A crummy little joke he thought nobody else would get. I could almost see him making that high-pitched laugh as he hit the register keys.

Like I said, good men die unjustly all the time. I’ve seen it happen to men a lot better than Sammy; there’s probably millions more I didn’t see it happen to. Life ain’t fair. Nobody knows that better than me.

But killing a guy like Sammy and joking about it? For the first time in a long time, I wanted to lash out at someone besides God. I wanted to feel my fist hitting the Bad Samaritan’s face, not stopping until I’d knocked out a few teeth.

I could do it. I just had to get to Mannheim’s fast, then wait outside until the killer showed up to finish the job … but with the twin mountains watching, I couldn’t do jack.

Or could I? I stared down at the hot plate, thought about the tenement fire … Damn. I still wasn’t getting anything to eat.

“Here’s the deal.” I stood up, spilling soup—trust me, it couldn’t hurt that carpet—and holding the burner as if to throw it. One of them started reaching for his gun, reconsidered what would happen if he shot me and I let go. He froze. “Either you let me walk out of here or I burn down this fleabag motel—and you two—and walk away whistling.” I wouldn’t walk out in any shape to whistle, but hopefully they didn’t know that. “Get out of my way or burn—your choice.”

Neither mountain moved. “Look, guys, we got two alternatives. If I’m not the killer, there’s no problem letting me amscray, right? If I am—well, you’re going to call Lansky soon as I go, right? There’s no way he’s gonna let me get to Rebecca.”

So help me, one of them actually showed an expression. Sour as a lemon, in case you were wondering. His eyes met his brother’s and he nodded to me. “Make your play. Later, we’ll make you sorry.”

“Later shmater.” The window would have been quicker, but there was no fire escape. I moved to the door. The mountain stepped away. “If I see you any time before I get out of here, I drop it.”

In the hall, I slammed the door shut, locked it—the lock would easily hold them for a couple of seconds—and raced to the stairs. On the ground floor, the desk clerk started babbling about illegal hotplates; I had a feeling I’d need a new apartment if the world didn’t end.

I got outside, dropped the damn thing in a gutter before it burned my hand, then took off.

I didn’t know Mannheim’s address, but I didn’t need to. The papers a few weeks back had played up a society murder in the skyscraper next to his, one that had drawn gawkers from all over town. All I had to do was ask the cabbie for the address of the DuBois killing, shell out more of my money for the ride, and I’d be there, waiting for the Bad Samaritan.

— ♦♦♦ —

Standing drenched in an alley, I stared across the street at Mannheim’s building, like I’d been doing for the last hour.

The mountains hadn’t wasted any time calling Lansky. I’d seen a dozen obvious mobsters in the lobby and on the street when the taxi dropped me off. A cop had tried arresting one of them for vagrancy, until a good-sized bill changed hands; I’d no doubt the staff in the lobby had been similarly greased.

I’d seen no sign of the Bad Samaritan and there couldn’t be more than about forty-five minutes to the deadline. Was Howard wrong about that? Had the killer seen the odds and backed off? What if he just decided to wait and start all over again with the new generation of Wufniks?

I was kicking myself for getting half-drowned just for a chance to slug the guy when a block-long limousine pulled up to the curb. The building doorman rushed to the side of the car, bowing, scraping and holding an umbrella, then the limo drove away, revealing the Bad Samaritan under the umbrella. Applying a gold lighter to a cigarette, he went inside before I could think what to do.

I could tell that the doorman knew the guy. If I ran over and tried to convince Mannheim or the mobsters that someone living in that skyscraper was the killer they didn’t believe existed … I hissed some curse words then that I hadn’t used since Masada fell. If he got up to the penthouse, one shot was all it would take. Even if Howard was wrong about the effect of killing the Lame Wufniks, Rebecca would be dead at the hands of that giggling putz.

Unless I got up there to stop him. Waiting in the alley, I’d thought of a way, but I didn’t much like having to try.

I crossed the street, hoping Lansky’s guards didn’t spot me before I made my way around to the neighboring skyscraper’s service entrance. Slipping a guy my last five and hinting I wanted to see the now-empty DuBois penthouse got me inside; I’d figured I couldn’t be the first person to sneak a peek at the murder site. Another fifty cents, leaving me less than a buck, got me the use of a phone. I called Kearney, but the stream of profanity gushing out of the receiver made it clear he wasn’t going to help.

A few minutes later, I stepped out of the service elevator onto the roof. I stared across the alley at the thick shrubbery that shielded David Mannheim’s sanctum from the prying eyes of city sparrows. Tommy Dorsey’s music blared loudly from somewhere in the penthouse, the band playing as if a girl’s life—maybe the world itself—wasn’t at stake.

There was no way to reach it, except to jump. It wasn’t impossible with a running start, but few people would have risked it twenty-five stories up.

Few people know they’re going to live forever. I might break every bone in my body if I fell, but I’d survive. Or I might land in a pile of trash and get off without a scratch; with my curse, living is the only guarantee.

For a second, I wondered why I was doing this. If they did end the world, my curse ended too.

But much as I wanted to stop wandering, I didn’t want it enough to let a nice girl die. God had stuck her with the burden of being a Lame Wufnik. The Bad Samaritan had killed her pop and laughed while he did it. Somebody had to be in her corner.

Shucking off my coat, I backed up to the far side of the roof, trying to ignore the rain, and broke into a run. I reached the edge, flung myself up and over and felt my stomach scream that this was a horrible, horrible mistake.

I landed on the Mannheim parapet with an impact that jarred my teeth, felt myself slide of the rain-slick surface, caught the edge of a heavy planter and stopped. I waited, ready for someone to peer through the bushes and shove me off, but Tommy Dorsey must have drowned me out. I got myself to a secure position and poked a space through the shrubbery.

It turned out Mannheim had good reason to want privacy.

Under a small tented pavilion outside the penthouse French doors, Rebecca lay, unmoving and naked, on what looked suspiciously like some sort of altar. The Bad Samaritan stood next to her, tapping his feet to the music, smoking and leering at Rebecca’s naked body.

I had no gun, no answers, nothing except the advantage of surprise. I figured I might as well use it. Stepping through the bushes I walked over to the pavilion.

“You!” The Bad Samaritan yanked out his automatic, eyes bulging. “David! Sharon! It’s the Wandering Jew!”

They were out through the French doors in a second, a couple of armed guards in their wake. I forced a smile. “Well, David, this is a shock,” I said. “I thought I’d have to sneak in here and finish her, but it looks like you’re doing my dirty work for me.”

“What the hell?” Sharon Mannheim said, staring at me. “You saved her life!”

“Before Howard told me what was at stake.” I shrugged, off-hand, keeping my best poker face on, then glanced down at Rebecca. “I don’t know why you want the world to end, but you can’t want it more than I do, lady. I came here to complete the Bad Samaritan’s job; I didn’t realize I didn’t have to.”

“You can’t!” Mannheim protested. “I mean, it may not be necessary—”

“Big brother, I owe him!” the Samaritan piped up, gun still pointed in my direction.. Now that he’d said it, I could see a slight resemblance. “Why don’t I just toss him over the edge of—”

“It won’t do any good, Peter,” Sharon said patting his arm. “I know he hurt you, but all we need to do is stop him from killing her until we know it’s necessary. Too many of them dead and—”

“Too many?” I asked. “For what?”

“That’s none of your concern, Mr. Soares,” Sharon said. “We’ll kill her, with the prescribed ritual, if it’s necessary, which we’ll know in about fifteen minutes. If it is, I think you’ll make a perfect ‘patsy,’ as they say in detective stories.”

Mannheim muttered something to his guards. They started forward. “No, wait!” his brother protested. “Couldn’t I just take a couple of shots? Just to pay him back, like?”

To my alarm, this time he was aiming at my gut. Mannheim nodded, Peter cocked the trigger—and then I heard a familiar bellow from inside the penthouse, sweet as the song of an angel.

“Mannheim, where the hell are you?” Shoving a servant aside, Kearney strode out onto the terrace with a couple of uniforms behind him. “Soares called, I figured it was baloney, but then a flatfoot reported a triggerman down on the street paying the beat cop to—”

He saw Rebecca and his jaw dropped.

With a desperate gasp, Peter Mannheim swung around, aiming at Kearney.

Before he could shoot, I started hitting him.

— ♦♦♦ —

“So I’m one of the Wufniks, and you’re the Wandering Jew.” Rachel’s hands were clenched tight on the bars of my cell. “I can’t quite—I’m sorry, I came here to thank you for saving me, not to … and how can that detective lock you up when you saved his life too?”

“Because I saved his life. He doesn’t like owing it to a Jew, particularly me.” I patted her hand. “Relax, it’s the best bed I’ve had to sleep on in years, and all Kearney could pin on me was trespassing. I’ll be out of here soon enough. But how are you taking it? Finding about your pop, and yourself, I mean.”

“Oh, swell. I almost got killed because David and his wife thought there was money to be made in killing half the Wufniks.” She said it with the shocked tone of someone who’d just realized how rotten people could be. “And I’m going to spend the rest of my life struggling as bad as Pop did, feeding moochers, and not even having a choice!”

The Mannheims had told Rachel enough before they doped her up that Howard felt he had to explain things afterwards. Apparently they’d figured that if they killed about half the Wufniks, God would be angry enough to withdraw his shekina—his compassion—from the world, and that next European war would be that much nastier and bigger. Mannheim hadn’t gotten in on the last war, but he was positioned to make millions off the next one.

“Are you sure you don’t have a choice, kid? Most Wufniks never know the score, as you do—“

“Only I am choosing this, Al.” She exhaled wearily. “People need food, people need help. If I can and I don’t, how could I sleep at night?”

You can learn, I thought, but I didn’t say it aloud. “Well I’ve got twenty centuries living with the short end of the lollipop. If you ever wanna talk—“

“Maybe next time you stop by the deli.” She managed a small smile. “After this, three squares a day for life wouldn’t be enough to say thanks.”

“Watch yourself. I’m going to live a long time.”

“Do they let people bring in food? I’ve never been to a jail before, but—“

“I’m being shifted to the other side of Brooklyn tomorrow. Meyer Lansky pulled some strings.” As long as I don’t stay three days in one place, the NYPD wouldn’t have to worry about earthquakes or thunderbolts destroying the building. “But don’t worry, I’ll be by to collect once I’m out.”

“My hero.” She managed a wan smile.

“Heroes change the world, I don’t. With or without Mannheim, the war’s going to come.”

“Heroes save lives, Al. You saved mine.”

“Yeah, but—“ I broke off. There was no way I was going to win the argument right now.

“Maybe you should try being a hero more often.” She picked up the handbag she’d left on a side table. “It’s a tough world, especially for Jews.”

“Jews have Zionists, they have Wufniks, they have the New Deal. If that doesn’t do the trick, what can one man do?”

I smiled as she left. Despite everything, she was still her father’s kid. At some level, even knowing what she knew, she probably did think one person could change the world.

A little whisper of conscience asked if she didn’t have a point.

After 2,000 years, why couldn’t that little voice just shut up?

END

Next Week:

“Nic Fits” by Adrian Ludens

Illustration by Sheik

3 Replies to “No Good Deed Goes Unpunished”